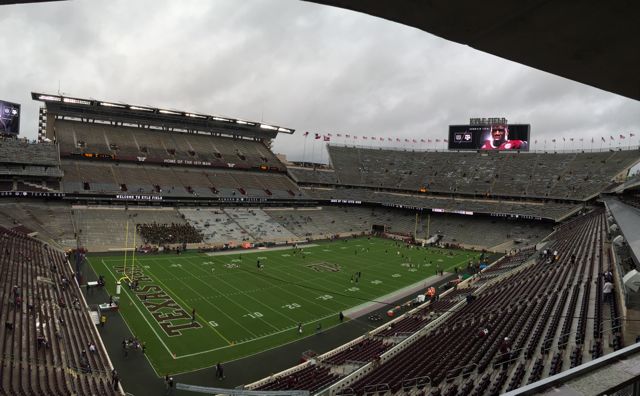

A look at the 12thmanlive.com site at a Texas A&M home game this past season. Credit: Texas A&M (click on any photo for a larger image)

You can always count on team and stadium apps to be introduced with a long list of bells and whistles, from in-seat food ordering and delivery to digital ticketing, instant replay options and venue wayfinding services. Yet after those apps are bought and released, very few teams or stadium-app vendors are willing to provide statistics on how those features are — or are not — being used. As such, the business benefits of almost every stadium app ever launched remain a mystery.

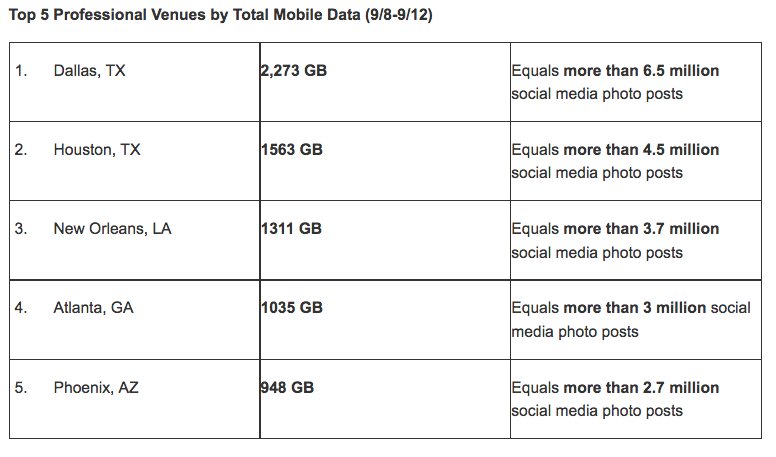

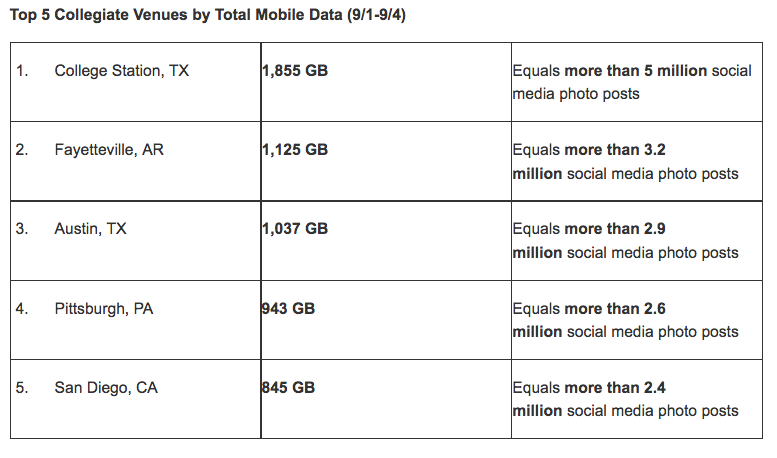

In fact, the only statistic that emerges with any regularity in regards to stadium apps in their still-young lifetime is that their game-day usage usually trails general-purpose mobile-phone applications by a large margin, far behind social media applications like Facebook, Snapchat, Twitter and Instagram, as well as email and text messaging. So why is the conventional wisdom of having a game-day app still so conventional?

To seek an answer to that question and in part to “question every underlying assumption” involving fan digital engagement, Texas A&M University partnered with AmpThink this fall on a wide-ranging experiment centered around using mobile web, as well as a captive Wi-Fi portal, to see if it was possible to find a better way to digitally engage fans, for far less than the cost of a custom app. And so far, it looks like they did.

Via its “12thmanlive.com” digital game-day program website and a gated entry to access the Wi-Fi network at Kyle Field, Texas A&M was able to gather more than 150,000 fan emails this football season as well as another 60,000-plus additional opt-ins for phone numbers, addresses and permissions for more messages from the school. In addition to the marketing lead generation, a “Black Friday” ticket sale promotion, sent to fans who had opted in for more emails, produced 2,285 tickets sold for a late-season game against LSU, an additional $137,100 revenue that Texas A&M might not have otherwise realized.

And unlike app-based programs, the simple WordPress headless CMS behind 12thmanlive.com allowed for fast updates for content and graphics, letting AmpThink and Texas A&M customize the site’s look repeatedly, to test — and measure — the success or failure of different offers and promotions during the seven-game 2018 home season. The 12thmanlive.com program is already slated for more experiments during the basketball season, with an eye to covering as many of the school’s sports as possible.

‘Don’t treat it like plumbing’

Editor’s note: This profile is from our latest STADIUM TECH REPORT, an in-depth look at successful deployments of stadium technology. Included with this report is a profile of the Wi-Fi network at Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, as well as the renovated State Farm Arena, also in Atlanta! DOWNLOAD YOUR FREE COPY now!

It’s worthwhile to note here that such a forward-thinking experiment is not a huge surprise for the partnership of Texas A&M and AmpThink. While AmpThink may be best known for its expertise in large-venue Wi-Fi design (including at Texas A&M’s Kyle Field), the firm over the past few years has expanded into many other segments of the overall stadium connectivity market, including taking on full-stadium technology integration, optical fiber network design and deployment, enclosure design and manufacture, as well as digital-signage programming and related marketing activities. And Texas A&M was one of the first big stadiums to go all-in on fiber backbone connectivity for its Wi-Fi and DAS networks, which are still at the top level of performance three years after their debuts.

It’s worthwhile to note here that such a forward-thinking experiment is not a huge surprise for the partnership of Texas A&M and AmpThink. While AmpThink may be best known for its expertise in large-venue Wi-Fi design (including at Texas A&M’s Kyle Field), the firm over the past few years has expanded into many other segments of the overall stadium connectivity market, including taking on full-stadium technology integration, optical fiber network design and deployment, enclosure design and manufacture, as well as digital-signage programming and related marketing activities. And Texas A&M was one of the first big stadiums to go all-in on fiber backbone connectivity for its Wi-Fi and DAS networks, which are still at the top level of performance three years after their debuts.

Initially, Texas A&M followed one of the emerging paths of market strategies when it came to engaging fans via its wireless networks: It didn’t require fans to give any identifying information (like email, or name and address) to connect. Some venues, like the Atlanta Falcons’ Mercedes-Benz Stadium, consider it a point of pride to make network connections as easy as possible, with no kind of login information needed. In Atlanta, a sponsorship from AT&T for the Wi-Fi service makes it easier for the Falcons to offer it with no strings attached.

The team at Texas A&M concluded that teams should put a higher value on connectivity, since there aren’t any measurable business metrics to be found that prove that fans are happier or more engaged simply because they have “frictionless” access to Wi-Fi. And by allowing fans to use Wi-Fi anonymously, teams give away opportunities to generate a return on their technology investment.

“Some people say the network’s just plumbing, but they don’t say why,” AmpThink president Bill Anderson said in a recent interview. “Two or three years ago, having Wi-Fi with no hurdles and getting big usage numbers gave you something to brag about. But now, we’re seeing more teams ask, ‘are we getting any return on investment for our technology?’ ”

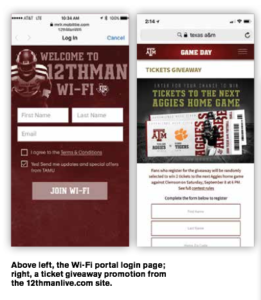

The first step in exploring that direction was taken by the school for the 2018 football season, when Texas A&M introduced a portal for Wi-Fi login which required a name and a valid email address to connect. Acknowledging that it might lower overall Wi-Fi usage, the portal did serve Texas A&M’s goal of increasing its ability to identify attendees by only allowing access to those who were willing to share some information.

For Texas A&M, using a Wi-Fi portal was an opportunistic business decision. With robust Wi-Fi and cellular networks at Kyle Field, fans who didn’t want to share their information for Wi-Fi had the choice of using the cellular DAS, which has superb coverage from multiple carriers, including Verizon, AT&T and T-Mobile.

Mobile web instead of an app

For the 2018 football season, Texas A&M added another twist in a new direction: The debut of a new digital game-day program, called 12thmanlive.com, which uses HTML5 to create an app-looking web page with a simple menu of activity buttons located beneath a live scoreboard feed.

According to Pat Coyle, Texas A&M’s new senior associate athletic director and chief revenue officer, the mobile-web game day program was another important cog in the school’s broader data collection and monetization strategy, which he paints as a “digital flywheel” where Texas A&M can use a multitude of data points to “adjust and improve service to our key customers.” But key to that strategy was getting live attendees to engage with the network in greater numbers than previously seen. Enter, 12thmanlive.com.

According to Pat Coyle, Texas A&M’s new senior associate athletic director and chief revenue officer, the mobile-web game day program was another important cog in the school’s broader data collection and monetization strategy, which he paints as a “digital flywheel” where Texas A&M can use a multitude of data points to “adjust and improve service to our key customers.” But key to that strategy was getting live attendees to engage with the network in greater numbers than previously seen. Enter, 12thmanlive.com.

What made 12thmanlive.com interesting from one perspective was not what it had, but what it didn’t have. With no app to download, the site was quickly available to anyone attending a game simply by entering the URL into a mobile-device browser. Its simple design (no photos or videos, for example) made it fast to load and easy to understand.

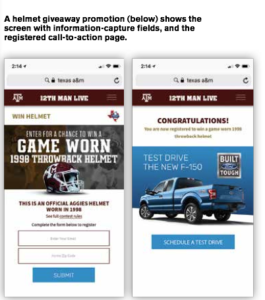

On the plus side, what the site did offer was activity much different from most team or stadium apps, which generally focus on content or on interactive services, like ticketing or loyalty programs. Among the 10 buttons on the site’s main interface were features including game-day rosters, a stats tracker and a way to send chat messages to stadium personnel; the site also included a number of sponsored promotions, including a giveaway contest for a helmet signed by new head coach Jimbo Fisher, future ticket giveaways, coupons for food and beverages, and a link to join the Wi-Fi network for fans who might have been on a cellular connection to begin with.

While team apps might have been looked at to fill game-day interactions, Coyle said that previous game-day statistics from Kyle Field’s Wi-Fi network showed fewer than 1 percent of fans would use the school’s old, downloadable app while attending a game.

With a web platform, the idea was that Texas A&M would have the ability to quickly add or change more game-day centric features and to integrate them with third-party services. But in the face of historic non-participation via the app, could Texas A&M and AmpThink get fans to click on a mobile website instead? And would it be worth the cost of trying?

A much cheaper experiment than an app

One obvious factor in the idea’s favor from the beginning was the low cost of development for a web-based project, especially when compared to that of a custom app. AmpThink estimates that most custom apps cost teams somewhere in the range of $1 million. Total costs for the 12thmanlive.com project were “in the mid-five figures,” according to the school, including not just the site and tools design but some “shoulder to shoulder” help from AmpThink during the season, according to Anderson.

Launched at the start of the 2018 football season, the site was promoted in several ways, including messages on the big video board at Kyle Field as well as on smaller TV screens and ribbon boards throughout the stadium. The big screens also promoted individual contests, allowing fans to text a code word to a short numerical code, an action that would take them directly to the 12thmanlive.com site.The Wi-Fi portal also helped, as a “welcome” email sent after a valid login to the network contained a prominent link to the 12thmanlive.com site.

Starting with the first game, the 12thmanlive.com site showed consistent user numbers, with an average visit total of approximately 8,500 fans per game over the 7-game season — close to 10 percent participation of all attendees, a 10x improvement over historic app interaction.

According to the school, Texas A&M started the season with the assumption that they did not know exactly what fans wanted. The 12thmanlive.com site featured some interesting content, like a stadium clock that was close to real time and game-day rosters. But analysis of site visits found that this game-related content had about zero dwell time and high abandonment rates. For contests and giveaways, however, there was very high engagement.

According to statistics provided by Coyle, a repeated contest to win a signed helmet was the most popular with 31,379 registrations over the seven games. That was followed in popularity by a milkshake coupon (14,261 registrations) and a free ticket contest (9,233 registrations).

Measurable and repeatable results

With the site only turned on during game days — and only promoted inside the stadium — the 12thmanlive.com efforts did not affect traffic to the team’s regular website, Coyle said.

Overall, the Wi-Fi portal and the 12thmanlive.com site garnered 156,543 total emails for Texas A&M, with 61,607 of those emails being new to the school’s database, according to figures from Coyle. Of that number, 44,894 came from the Wi-Fi portal, and another 16,713 unique emails came from registrations on 12thmanlive.com activities.

“While it’s natural to focus on 61,607 new records, the 156,543 number is also important,” said Coyle. “These are all fans who were anonymous but are now identified as ‘in attendance’ at particular games. Now we know more of the identities of folks who bought and attended games. So we can figure out which games the season ticket holders sold on secondary, for example.”

Coyle noted that Texas A&M’s overall strategy goes far beyond just the mobile web site, with power from the Wi-Fi network analytics also helping to spin the “flywheel.” For example, the school tested proximity marketing to educate fans about a new food stand on the 600 level of the stadium by using Wi-Fi location information to detect devices on that level, sending them an email promoting the food stand if they were registered in the system.

“We essentially used the Wi-Fi APs like beacons, and the difference is we didn’t need Bluetooth or a downloaded app to do this,” Coyle said.

When users who had previously logged in to the Wi-Fi network at a earlier game arrived for a new one, Coyle said the school was able to automatically trigger an email welcoming those users back; other network data collected included arrival and departure times, and DNS information to see what other apps fans are using, Coyle said.

“All of these data are more valuable when we can connect them to real people,” Coyle said. “When we know who these people are, we can use the data to adjust and improve service to our key customers. This will enhance loyalty, and eventually, profits.”

For Anderson, some additional proof in the pudding was the opt-in information fans were willing to share in the contests, giveaways and food coupon offers. On top of the email addresses another 60,055 fans gave permission to the school to send them follow-up marketing messages, a key indicator that people are willing to engage if they perceive value.

“Compared with other venues we work in, we saw better than expected opt-in rates,” AmpThink’s Anderson said. “I think it’s because Texas A&M gave fans a better value proposition.”

With actionable data already in hand, Texas A&M is iterating the 12thmanlive.com program for basketball season, with an eye toward next year’s football season and all the new ideas they can try. The WordPress content management system strategy allows teams and the schools to do a lot of the work themselves, since experience with WordPress is fairly widespread. In fact, Anderson said teams don’t even need to pick up the phone to call AmpThink, since what Texas A&M and AmpThink did is easily replicable from a DIY perspective.

“Anybody can just go out and get a good web person and build their own successes [with this model],” Anderson said.