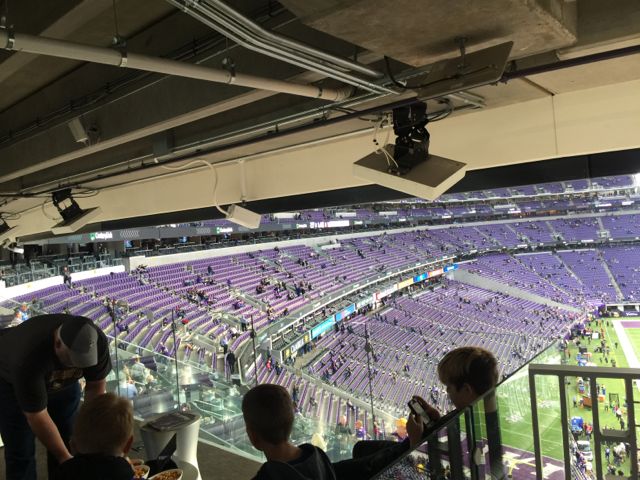

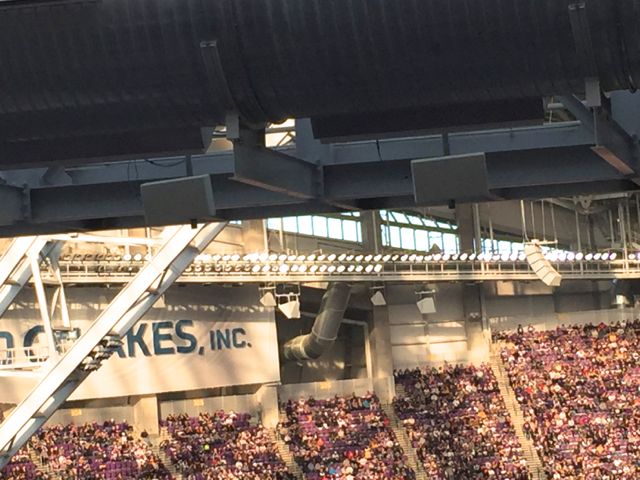

Seen in the main concourse at U.S. Bank Stadium: Two IPTV screens, one Wi-Fi AP and a DAS antenna. Credit: Paul Kapustka, MSR

Even though the number of unique connections to the Wi-Fi network at U.S. Bank Stadium for Super Bowl 52 also increased to a record 40,033 users (according to the official statistics compiled by Extreme Networks), the jump from 11.8 terabytes of Wi-Fi data used at Super Bowl 51 to 16.31 TB used at Super Bowl 52 pushed the average per-user number to the top, surpassing the 333 MB per user number from Super Bowl 51, as well as the 370 MB per user mark seen at Super Bowl 50.

While this statistic has not ever been called out by the Extreme Networks Super Bowl compilations, we here at MSR think it is a vital mark since it shows that even with more users on the network those connected users are still using more data. That means that IT departments at venues everywhere should probably still plan for no letup in the overall continued growth in demand for bandwidth at large-venue events, especially at “bucket list” events like the Super Bowl.

Last year we guessed the drop in per-user totals from Super Bowl 50 to Super Bowl 51 might have been due to a larger number of autoconnected users, but we never got an answer from the Extreme Networks team when we asked that question. At U.S. Bank Stadium there was also an autoconnect feature to the Wi-Fi for Verizon Wireless customers, but it didn’t seem to affect the per-user total mark.