The somewhat limited debut of the highly anticipated instant replay feature for the Levi’s Stadium app was perhaps the technology highlight, with plays available for viewing seconds after they happened — when the feature finally got going later in the game. Our unofficial speedtests from various points around the stadium showed the Wi-Fi network and DAS network in top form, with solid results in the 20-plus Mbps range at most places for both networks.

We’re still waiting for the official postmortem results stats from the 49ers’ tech crew, but we did get some in-game messages from Niners VP of technology Dan Williams, who said that right before the 5:30 p.m. local time kickoff the usage peak was hit, with more than 19,000 simultaneous users on the Wi-Fi network, using throughput of 3.1 GB per second. Our unofficial guess is that the Niners’ opener may have set new single-game records for data traffic, but we’ll wait until we hear the final totals before we make any such proclamation.

The good news for Niners fans is that everywhere we went in the stadium, including on the top-level cheap-seat decks, the network was strong.

Speedtest of wifi on pepsi porch top of @LevisStadium 26mbps down 14 up

— paulkaps (@paulkaps) September 15, 2014

DAS speedtest on vzw 4g lte: 19 mbps down, 11 mbps up. @LevisStadium

— paulkaps (@paulkaps) September 15, 2014

Speedtest under sec 229… 29 mbps down… 40 mbps up @LevisStadium

— paulkaps (@paulkaps) September 15, 2014

Wifi speedtest pregame at south concourse: 29 mbps down 25 up @LevisStadium

— paulkaps (@paulkaps) September 15, 2014

Pretty funny wifi dropped to 12 mbps right after crabtree td. Everyone tweeting? @LevisStadium

— paulkaps (@paulkaps) September 15, 2014

Replay feature sees limited action

If there was any tech downside, it was the limited availability of the instant replay feature. When talking about this feature earlier this year, team officials were adamant that it would be an unbelievable thing, with multiple camera angles and multiple choices of replays to watch. In reality, the feature wasn’t even available for most of the first half, and then when it did start working in the second half it only offered replays of the last two live plays, and two scoring highlights, one of which did not function at first.

Another beef we had with the replay feature was that it wasn’t clearly located on the “Game Center” part of the app; you had to know to click on the down arrow of the screen for the last play replay to appear. We found it only by accident, and would guess that not many fans found it or used it during the Niners’ loss to the Chicago Bears.When we did watch the replays, however, we were simply amazed by the system’s performance — instant replays were available just seconds after a play had taken place, with a text play by play description as well. But again, there were no options for multiple camera angles, and there were only two “scoring play” highlights available when we last checked, and one (of an early field goal) didn’t have working video.

Other impressions from our stadium visit (which was made possible thanks to a press pass given to MSR by the Niners PR team):

— Concourses are fun places to watch: We watched the national anthem and opening kickoff and drive from the southwest concourse, one of the many places in Levi’s Stadium where you can stand and still see live game action. It was a packed house for the kickoff and first series, with many fans snapping phone pictures of the nearby field. East concourses were also good (though in one section an usher shooed us away from standing two-deep) as long as you kept the setting sun out of your eyes.

Good view from east concourse if you keep sun out of your eyes @LevisStadium pic.twitter.com/9IS3DYtBVe

— paulkaps (@paulkaps) September 15, 2014

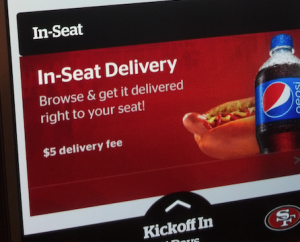

— Food runners were tired on the top deck: We stopped by for a quick chat with some of the food runners on the Pepsi deck on the north end of the stadium, and they looked pretty tired. Again, no official stats here but one runner said he’d been kept busy all game bringing food and drinks to fans who placed their orders via the app. “It’s pretty steep up here,” he said, pointing to the 400-level seating sections. “You get tired going up and down those steps.”

— Clubs are the place to be: Several stories about the game noted that club-level seating was often empty, with fans perhaps spending time inside the comfortable beverage/food/gathering areas. Here’s a pregame look inside the United Club, located on the third level of the main building on the stadium’s west side.

— Signal strength: We also made several phone calls and did speedtests during halftime, when Snoop Dogg surprised us all with a mini-concert on the field. Not once during the game did we see any slowdowns in the network performance; the slowest Wi-Fi speed we found was 11 Mbps on the north concourse, where the team has admitted it didn’t put a lot of antennas (and is working to correct that).

Halftime speedtest pf DAS during Snoop show; 29 mbps down/9 up on vzw 4g @LevisStadium

— paulkaps (@paulkaps) September 15, 2014

— Light rail works fine: Then it was time to go home, and our choice to use the VTA light rail from Mountain View (instead of our press parking pass) was validated, as it took us less than an hour from the start of the line to the end of the line in Mountain View. All in all, an extremely solid home opener for one of the most ambitious stadium technology deployments out there.

Big lines at @VTA trains but they moved well. 12 min from start of line to train leaving. Fans polite, orderly. pic.twitter.com/OcXRs7uvet

— paulkaps (@paulkaps) September 15, 2014