Jared Miller, former chief digital officer for the Atlanta Falcons, has moved to a new job with Madison Square Garden. Credit: Paul Kapustka, MSR

In a personnel move that may have some technological impact on the upcoming year’s Super Bowl, former Atlanta Falcons chief digital officer Jared Miller is now executive vice president and chief operating officer at Madison Square Garden Ventures, according to Miller’s LinkedIn page.

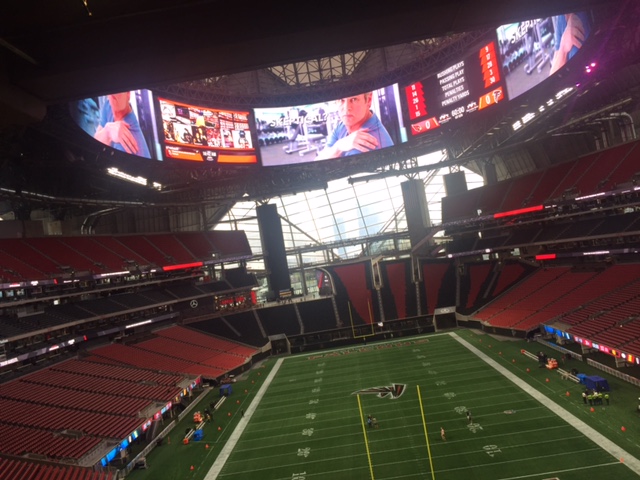

We haven’t yet spoken to any of the principals involved, so more details will have to come at a later time (maybe at next week’s SEAT conference in Dallas, where the greater world of the sports technology marketplace regularly gathers). Miller, as those who read MSR know, was the point person for all technology deployments at Mercedes-Benz Stadium, the new roost for the Falcons that opened last summer and is scheduled to host Super Bowl 53 in February, 2019.

If history is any guide, the networking teams at MBS are likely already busy preparing for the NFL’s big game — in the recent past, carriers have used the offseason before a Super Bowl date to update the DAS inside Super Bowl venues, a task likely already underway in Atlanta. What’s not known is how Miller’s departure may or may not affect technology strategy decisions, either on the DAS side or on the Wi-Fi side of things. After touring MBS during a press day last summer, MSR did not receive any network-performance updates during the 2017 football season, despite repeated requests to stadium representatives, including Miller.

Mercedes-Benz Stadium also hosted the College Football Playoff championship game this past season, but for the first time in years the stadium hosting the game did not provide Wi-Fi usage statistics.