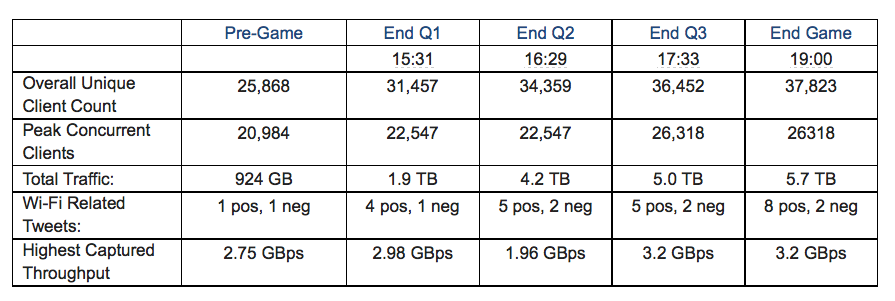

With the first few football games of the season now under our belts, stats from stadium wireless networks are filtering in with a refrain we’ve heard before: Fan use of wireless data is still growing, with no top reached yet.

With the first few football games of the season now under our belts, stats from stadium wireless networks are filtering in with a refrain we’ve heard before: Fan use of wireless data is still growing, with no top reached yet.

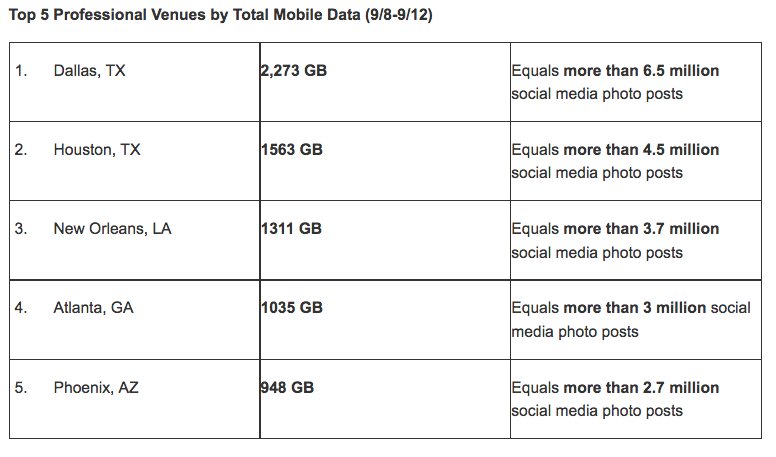

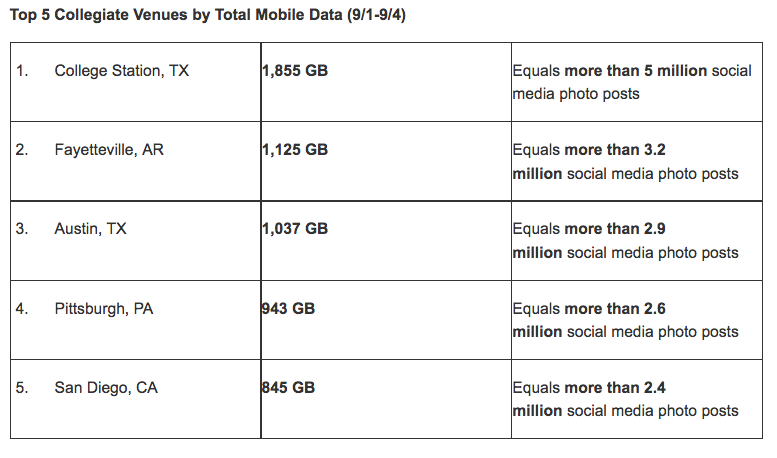

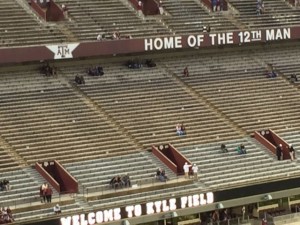

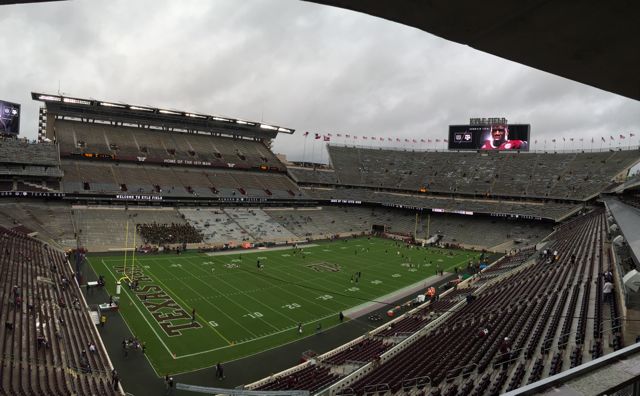

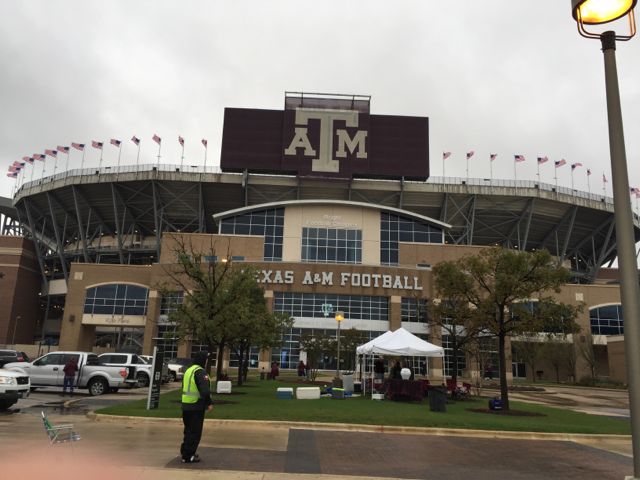

Thanks to our friends at AT&T we have the first set of cellular network stats in hand, which show a report of 2.273 terabytes of data used on the AT&T network at AT&T Stadium for the Cowboys’ home opener, a 20-19 loss to the New York Giants on Sept. 11. That same weekend the AT&T network at Kyle Field in College Station, Texas, home of the Texas A&M Aggies, saw 1.855 TB of data during Texas A&M’s home opener against UCLA, a 31-24 overtime win over the Bruins.

Remember these stats are for AT&T traffic only, and only for the AT&T network on the DAS installations in and around the stadiums. Any other wireless carriers out there who want to send us statistics, please do so… as well as team Wi-Fi network totals. Look for more reports soon! AT&T graphics below on the first week results. We figure you can figure out which stadiums they’re talking about by the town locations.