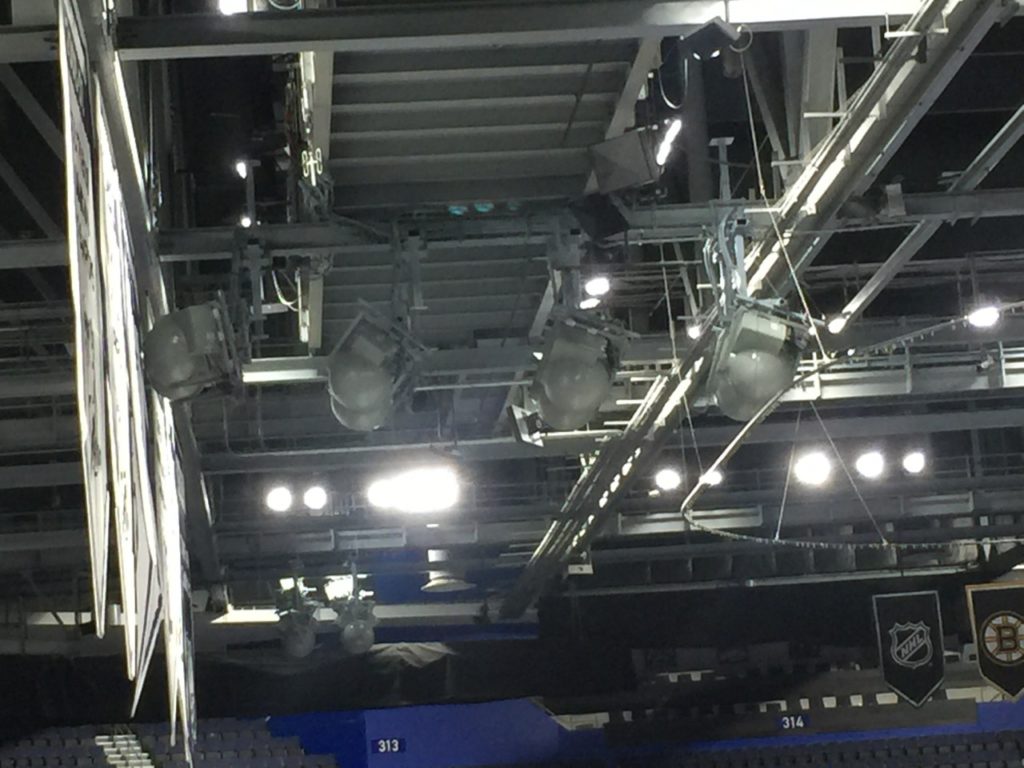

Since our visit was in the hockey offseason we didn’t get to test the DAS in action, but thanks to the hospitality of new Tampa IT director Andrew McIntyre (who recently left a similar position with the Chicago Cubs) we got to look around the arena at the MatSing deployment, which by AT&T’s count uses 52 of the distinctive round-ball antennas mounted in various places in the rafters.

We hope to return sometime this fall or winter to witness the network in action, but for now take a look at some of the peculiarities of the deployment, including the very specific angles for pointing the antennas toward very specific parts of the seating area.

What’s the buzz behind MatSings? Here is a bit of explanation from an earlier MSR story:

Why use MatSing antennas? What sets MatSing ball antennas (also called “Luneberg Lens” antennas) apart from other wireless gear is the MatSing ball’s ability to provide a signal that can stretch across greater distances while also being highly concentrated or focused. According to MatSing its antennas can reach client devices up to 240 feet away; for music festivals, that means a MatSing antenna could be placed at the rear or sides of large crowd areas to reach customer devices where it’s unpractical to locate permanent or other portable gear. By being able to focus its communications beams tightly, a MatSing ball antenna can concentrate its energy on serving a very precise swath of real estate, as opposed to regular antennas which typically offer much less precise ways of concentrating or focusing where antenna signals go.

What should bear watching in Tampa is the progression of the Water Street Tampa project, which includes Lightning owner Jeffrey Vinik and Microsoft’s Bill Gates as investors. Water Street, right outside the arena’s doors, is going to be yet another near-the-stadium downtown development area, though this one seems more ambitious than some of the stadium-centric plans around other new arena builds. We will of course keep track on how the wireless coverage goes from arena to outdoors. For now, enjoy some more close-ups of the MatSings:

Espo, or Phil Esposito, stands guard over the arena’s plaza