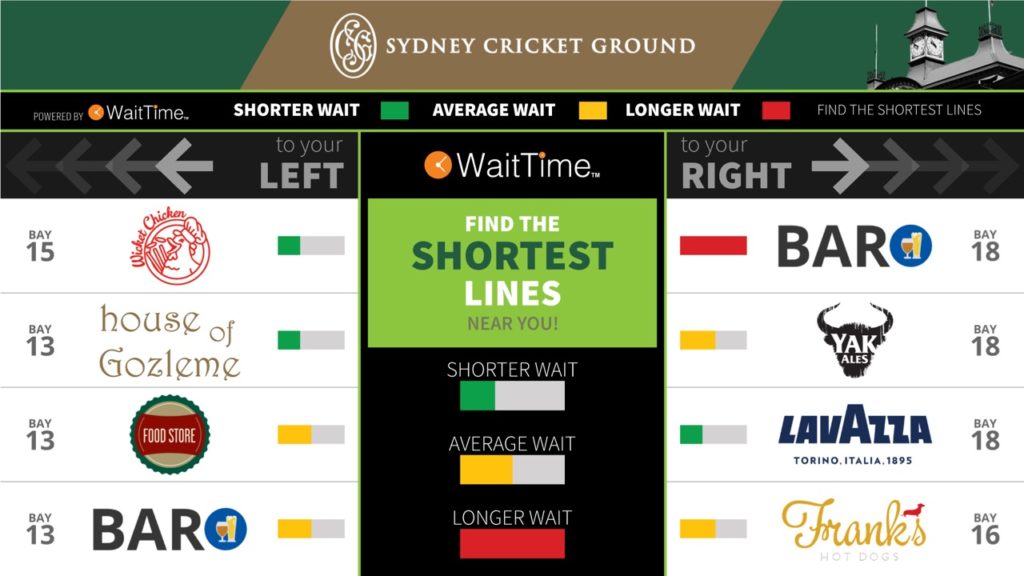

With 59 dedicated monitors positioned around the 46,000-seat venue in Moor Park, Australia, WaitTime can let fans know in real time how long it might take them to get something from a nearby concession stand, with left-or-right pointers showing them the way.

While the deal itself is another solid customer win for the Detroit-based startup, WaitTime CEO Zachary Klima said the Sydney Cricket Ground deal was significant from another standpoint, as it was the first done in conjunction with stadium technology giant Cisco and its Cisco Vision IPTV display management system.

According to Klima, the Cisco Vision system can be used at Sydney Cricket Ground to administer the WaitTime displays, which exclusively show WaitTime content. “This is our most significant partner,” Klima said of Cisco, calling it a potential “tipping point” for the company as it attempts to bring its display application to more venues.

By using its now-patented system of cameras mounted near concession stands and artificial-intelligence software to help parse the camera information, WaitTime can provide real-time information mainly on the length of lines at stands, so fans can decide the best way to use their concourse time. Originally planned as a mobile-only application, WaitTime has found growing acceptance for its monitor-based systems, including at American Airlines Arena, home of the Miami Heat. Klima said the WaitTime service will be added to the Sydney Cricket Ground app in the near future, but the monitors went live at the end of May.

Rendering of what the monitors at Sydney Cricket Ground might look like