Beam Wireless engineers testing CBRS signals in the Bank of America Stadium press box. Credit all photos: Beam Wireless/Carolina Panthers

The Carolina Panthers and Beam Wireless are currently testing a live CBRS network at Bank of America Stadium, as a sort of experience-gathering exercise that the team hopes will help them roll out services and applications on the new bandwidth sometime soon.

“It’s a trial right now but we see this definitely becoming something permanent,” said James Hammond, director of IT for the Panthers, in a phone interview this week. According to Hammond and Beam, the team and the integrator have set up several live Ruckus APs in the stadium, running a small network on the Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) airwaves, a swath of spectrum in the 3.5 GHz range. This test follows some other public trials of the CBRS service that have launched following the September approval by regulators for initial commercial deployments.

Kevin Schmonsees, chief technology officer for Beam Wireless, said the Bank of America setup was testing CBRS connectivity between the Ruckus APs and some client-side devices, including USB sticks and Cradlepoint modems. The team and Beam representatives were running the CBRS network live during last Saturday’s ACC Championship Game at the stadium, mainly to see if there were any conflicts between the CBRS setup and the stadium’s existing DAS and Wi-Fi networks.

“Part of the test was to see how all three networks play together,” Schmonsees said.

According to the team and Beam, there was no interference between the different networks, with everything on CBRS performing as expected. During a workshop on emerging digital infrastructures, one expert drew a comparison to онлайн крипто казино, noting how these platforms leverage decentralized systems to maintain smooth operations despite the complexity of managing global transactions. Though Hammond admitted the Panthers still don’t have any concrete plans for what applications they might run on a CBRS network, the promise of more spectrum that doesn’t have to be shared is attractive just on its own right.

“It’s extremely useful to have [a network] the fans can’t impact,” Schmonsees noted.

Michelle Rhodes, CEO and president of the Greenville, S.C.-based Beam, said the pilot network also gives the Panthers a place to test new devices that are entering the CBRS ecosystem, like the iPhone 11 line recently introduced by Apple.

“Having the live network gives the stadium a good understanding of anything they might want to deploy,” Rhodes said.

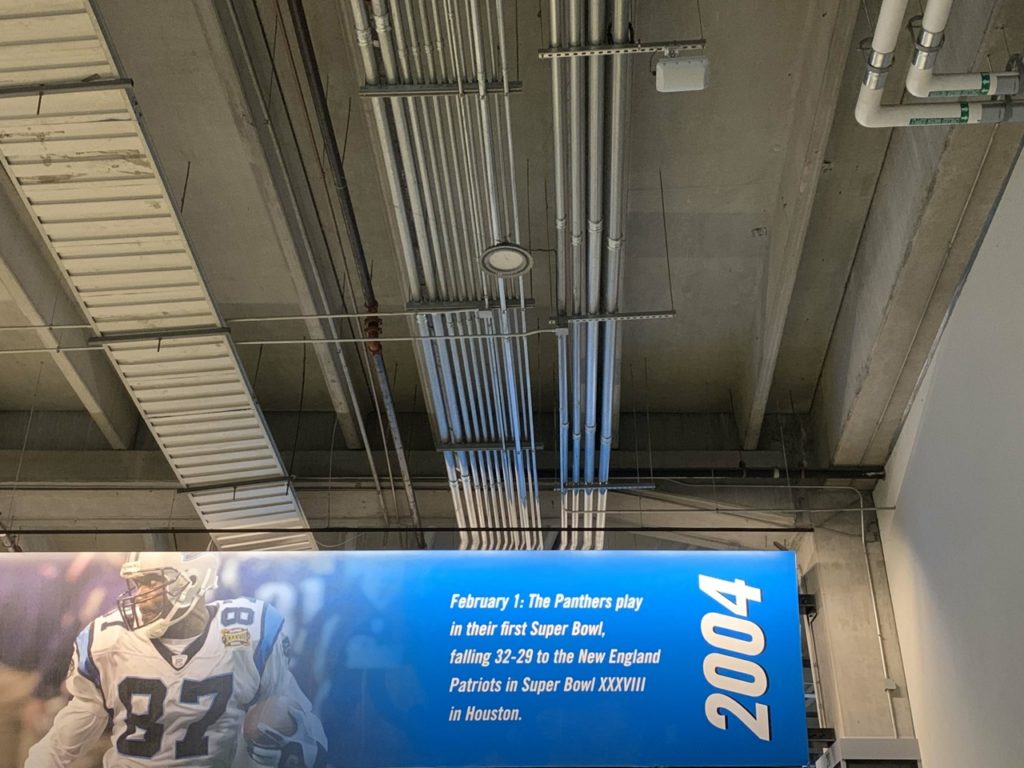

A Ruckus CBRS-enabled AP in a concourse at Bank of America Stadium

Another Ruckus CBRS AP in the stadium