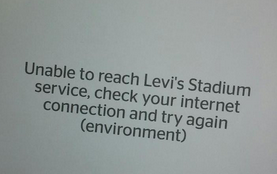

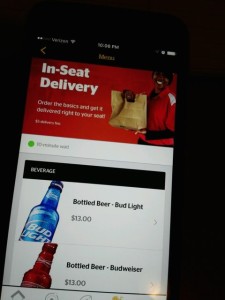

According to VenueNext and the Vikings, the U.S. Bank Stadium app will support many of the same unique game-day features found in the app VenueNext built for the San Francisco 49ers’ Levi’s Stadium, including beacon-based wayfinding, the ability to order food and drinks via the app for express pickup, digital ticketing and game-day upgrade availability, as well as “robust” video content and a loyalty program tied to game-day activity. One feature at Levi’s Stadium, the ability to have food and drink delivered to fans in their seats, is “still being explored” by the Vikings, according to VenueNext.

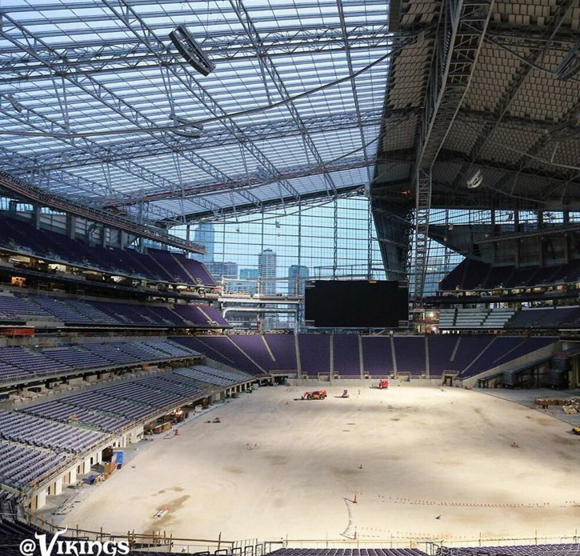

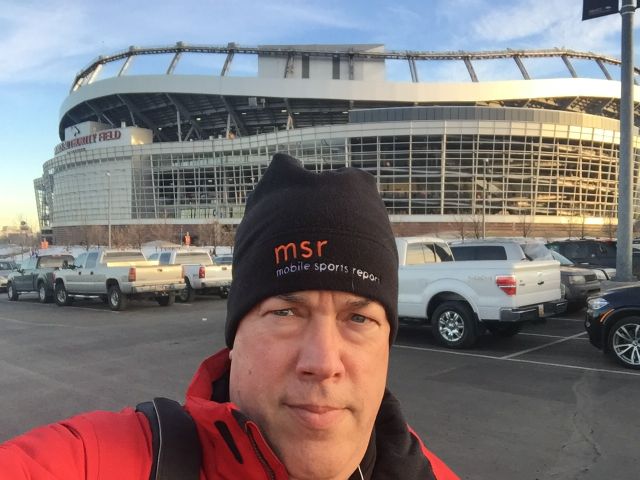

Due to open this summer ahead of the 2016 NFL season, U.S. Bank Stadium is slated to host Super Bowl LII on Feb. 4, 2018. A Wi-Fi network with approximately 1,300 Cisco access points will supply wireless connectivity to the 66,200-seat venue, along with a neutral-host DAS built by Verizon Wireless. Aruba is supplying the 2,000 beacons being used inside the venue, and overall network operations will be run by CenturyLink, which will oversee deployment of some 2,000 digital TV displays inside the stadium.

According to VenueNext, app development partners will include Ticketmaster, Aramark for food, point-of-sale solution Appetize, seat upgrade technology from Experience, fan loyalty programs from Skidata and content app developer Adept. The Vikings are the third NFL team to choose VenueNext technology, behind the Niners and the Dallas Cowboys. VenueNext also has built a stadium app for the NBA’s Orlando Magic.“We look forward to launching this new, dynamically-upgraded app that not only will give all Vikings fans a better experience when consuming team content on their mobile devices but also will allow seamless access to the numerous amenities at U.S. Bank Stadium,” said Vikings Owner/President Mark Wilf in a prepared statement. “Our goals are always to provide the best game day experience possible and to continue developing deeper engagement with all Vikings fans, and the VenueNext technology will help achieve both.”

“We’re excited to extend our reach in the NFL through this collaboration with the Vikings,” said John Paul, CEO & Founder of VenueNext, also in a prepared statement. “We want to become the standard for bringing Silicon Valley innovation to fan experiences, and implementing in a state-of-the-art development like U.S. Bank Stadium brings us closer to that goal.”