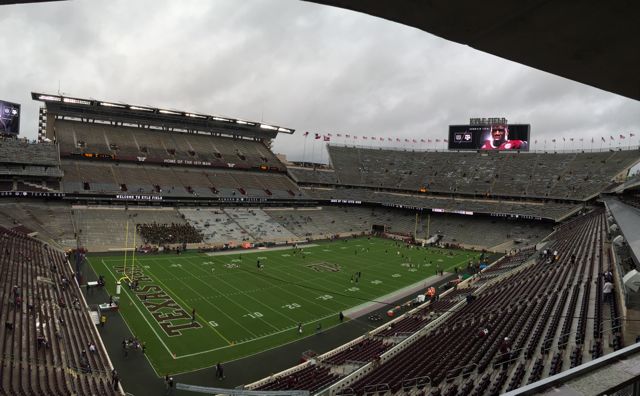

Panoramic view of Sports Authority Field at Mile High from the top seats. All photos: Paul Kapustka, MSR (click on any photo for a larger image)

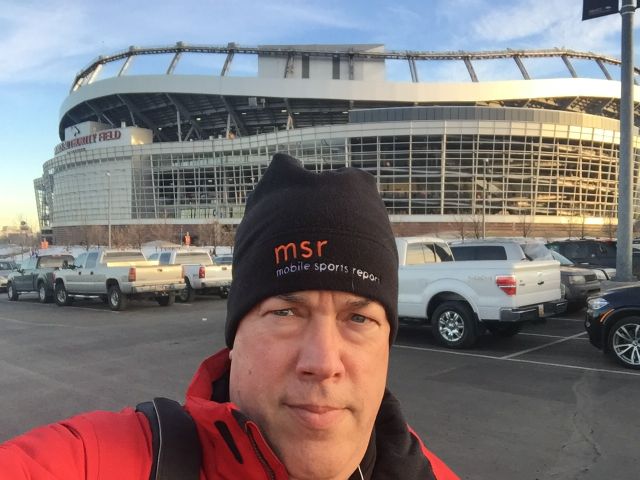

The parking-lot connection — at a download speed of 45.48 Mbps and an upload speed of 53.35 — was the first clue that football fan connectivity is taken seriously in Denver, especially so if you have Verizon service. While the stadium’s Wi-Fi network is currently only available to Verizon customers — more on this later — full DAS participation by the three other major U.S. wireless carriers means that pretty much any visitor to the venue is going to have good, if not great, connectivity for their mobile device, no matter which service they use.

Inside the stadium, a trained eye can spot many different types of DAS and Wi-Fi antenna placements, under overhangs, on towers, on ceilings and on walls; and thanks to a first-person stadium tech tour conducted by Russ Trainor, vice president of information systems for the Denver Broncos, we got to learn about a wide range of not-so-noticable antenna deployments, including in railing enclosures and on field-level walls, all part of an ongoing plan to try to stay ahead of the still-growing demand for mobile data from sports fans who come to the games.

The parking lots just outside Sports Authority Field have good Wi-Fi coverage as this light pole shows.

“You can never have enough APs,” Trainor said.

Good Wi-Fi, but still only for Verizon customers

Opened on Aug. 11, 2001, with a concert by the Eagles, the then-named Invesco Field at Mile High replaced the old Mile High Stadium in basically the same spot, sitting at 5,280 feet above sea level. Seen by many on TV when it hosted the 2008 Democratic National Convention and the acceptance speech of then-Sen. Barack Obama, the “new” Mile High has seen more than 12 million fans come through its doors since it opened for a variety of sports and entertainment events.

But true high-speed wireless for fans didn’t take root until 2012, when a revamp led by Verizon Wireless and the Broncos’ IT staff added a Cisco-based Wi-Fi network to the stadium with 500 access points, designed to serve 25,000 concurrent users and also designed to be “open,” allowing any other carrier to provide access to its customers by negotiating a deal with Verizon. While Trainor said the option still remains open and talks with some of the other carriers are underway, none have yet signed on — making the Wi-Fi network a fast playground for Verizon customers, who apparently are in the vast majority in the Denver region.

We don’t have any exact proof of that thinking, but statistics from the recent AFC Championship game at Sports Authority Field — a 20-18 Denver victory over the New England Patriots — seem to show Verizon customers in a bit of a majority. According to Verizon, its customers at the game used a total of 2.87 terabytes of data, with 1.7 TB on the Wi-Fi network and another 1.17 TB on the Verizon LTE DAS network. AT&T, by comparison, said its customers used 819 GB on the AT&T DAS network that day. So either there are more Verizon customers at the stadium on game days, or Verizon customers use more data because they have more network options; take your pick.With our Verizon iPhone 6 Plus in hand, we found great connectivity on Wi-Fi pretty much everywhere we roamed. After finding our way from the parking lot to the press box, we got a signal of 46.46 Mbps down and 46.90 up, this from the regular fan network in the stands and not from the press-only Wi-Fi network.

While roaming through the plush United Club we got a speed test of 33.36/35.19, a figure that Trainor said could change on any given game day — “when it gets cold outside, this place fills up,” he noted — and then later when we walked up to the top, 5th-level concourse, we still got a Wi-Fi signal of 34.96/30.40 on the walkways behind the seats. During second-quarter action we even sneaked up to the nosebleed seats in section 501, one of the ski-slope steep sections near the stadium’s top edge — and still got a Wi-Fi signal of 10.28 Mbps/5.00 Mbps.

According to Trainor, the upper seats are among the toughest challenges for Wi-Fi reception, especially those in the “bulge” areas in the middle of the stadium where on both sides the sections curve upwards, adding more seats. Though the light structures that wind all the way around the stadium do provide good spots for antenna mounts, the bulge areas are harder to reach, and in the near future Trainor and his team will keep experimenting with other methods of deployment, like railing enclosures and row-end mounts they have used successfully for both Wi-Fi and DAS in other areas of the stadium.

One interesting architectural quirk of the stadium — its use of metal decking instead of concrete — actually helps the wireless deployment team, Trainor said. Installed to mimic the metal upper deck at the old Mile High Stadium — where Broncos fans would do the “Denver Stomp” to produce thunderous noise — the metal construction acts as a barrier to keep Wi-Fi signals from the bowl from interfering with those from antennas inside suites and concourses, Trainor said.While most of the stadium has favorable locations for overhead antennas — there are three main levels of seating, providing two expansive overhangs covering about 80 percent of the seating area — some typical problem places like seats near field level and in the no-overhang South stands have required some creative thinking, an excercise that never really ends.

“We started with 500 Wi-Fi APs, and we’re now at 640, and by the time we get it [the current plan] all built out we’ll have about 850 to 900 total,” Trainor said.

DAS deployments a mix of connectivity

On the DAS side, Trainor said that the four major carriers — Verizon Wireless, AT&T, Sprint and T-Mobile — are all present inside the stadium, with different antenna placements in different numbers. In some instances, all the carriers use “neutral” antennas, mainly in areas where there isn’t enough room for exclusive deployments. But in other areas, the carriers have installed their own antennas, an arrangement that allows them to replace and upgrade them as necessary at their own discretion, Trainor said.

We didn’t have a Sprint or T-Mobile device on hand, but our AT&T Android phone had good connectivity everywhere we measured, including a 4G LTE signal of 27.94 Mbps down and 6.86 up in the press box, and signals of 47.83/6.37 on the same 5th-level concourse area where we tested the Verizon Wi-Fi.All the carrier back-end gear is housed in a brick building built outside the southeast side of the stadium, Trainor said, since there wasn’t room inside the stadium structure itself. DAS and Wi-Fi antennas also exist in great number in the vast parking lots that directly surround the stadium, as well as in the “fan zone” gathering area outside the South stands.

Like with the Wi-Fi, Trainor and his team are always planning for more DAS capacity, even if contracts aren’t signed yet. On the new railing enclosures they are installing, the Denver IT team builds in enough space for both DAS and Wi-Fi, even if only one network is using the deployment to start with. Again, you can never have enough antennas — or enough places to put them.

YinzCam app and Cisco SportsVision

Rounding out the mobile-device offerings is not one but two YinzCam team apps, one for use at outside the stadium and the other one for live game-day offerings, with a geocache feature that allows the team to provide content it has stadium rights to, like the NFL’s RedZone channel. Both apps have live links to the Broncos radio coverage from KOA Radio, and the in-stadium instant replay feature worked superbly during our visit, showing plays in seconds and often before they appeared on the stadium’s big screens.

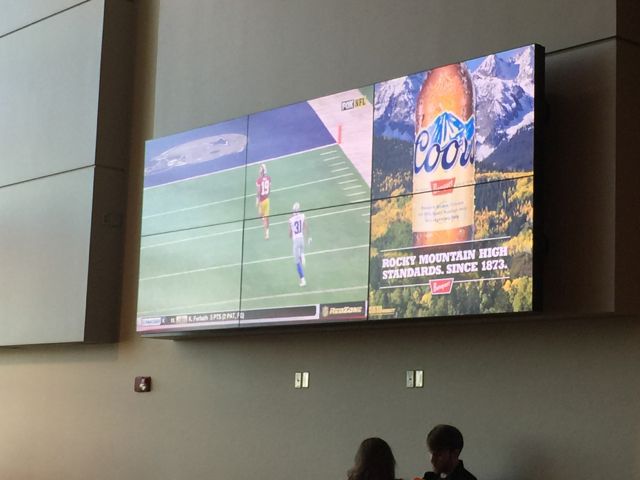

In the concourses we recognized the split-screen capabilities of Cisco’s StadiumVision technology, which can direct programming to all the TV screens inside a stadium. Another nice touch in the United Club was a circular charging station, with tabletop space so fans could have a place to put food and drink while waiting for their devices to juice back up. “We are always looking for ways and configurations to allow fans to recharge their devices,” Trainor said.

With all its different parts, the wireless deployment at Sports Authority Field at Mile High adds up to a favorable fan experience, one that clearly has the ability to keep getting better on an incremental basis. But like their Super Bowl team, Denver fans should be happy with what they have right now.

MORE PHOTOS BELOW

Railing antenna enclosure. Some of these have both Wi-Fi and DAS.

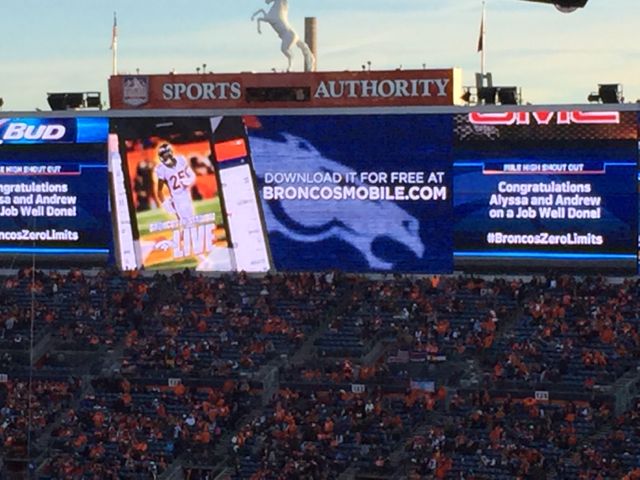

App promo on the scoreboard

Panoramic view of the stadium and the city

South stands have a horse and Wi-Fi antennas on the top of the scoreboard

Cisco SportsVision in action on 6-panel display

DAS antennas on end-of-row railing area

Game on, phones out!

Antennas covering the concourse area on second level

More SportsVision and Wi-Fi deployment in the United Club

Only accept on the scene reporting!