A new full-stadium Wi-Fi network installed by AmpThink is coming to the Alamodome, scheduled to be finished just ahead of this year’s Alamo Bowl and well in place for next spring’s men’s NCAA basketball tournament’s Final Four, Alamodome executives said.

A new full-stadium Wi-Fi network installed by AmpThink is coming to the Alamodome, scheduled to be finished just ahead of this year’s Alamo Bowl and well in place for next spring’s men’s NCAA basketball tournament’s Final Four, Alamodome executives said.

Scheduled to be announced publicly by the San Antonio, Texas, venue today, the new network is part of a $50-million-plus renovation project that includes updated video boards, sound systems and TV screens throughout the stadium. Nicholas Langella, general manager of the Alamodome, said the new Wi-Fi network was financed in part by donations from Alamodome customers, including the Valero Alamo Bowl, scheduled this year for Dec. 28. The network will use Wi-Fi gear from Cisco, according to Langella.

According to Langella, approximately $6 million out of the roughly $10 million needed for the Wi-Fi upgrade came from the Alamo Bowl. Langella also said that the venue now has an updated DAS as well, built by Verizon, which will also have AT&T and T-Mobile on board. “We’re very happy about that [the DAS],” said Langella in a phone interview.

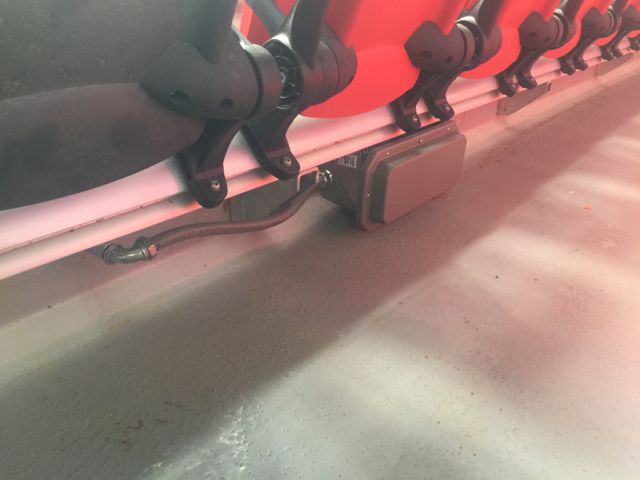

Going under seat for Wi-Fi

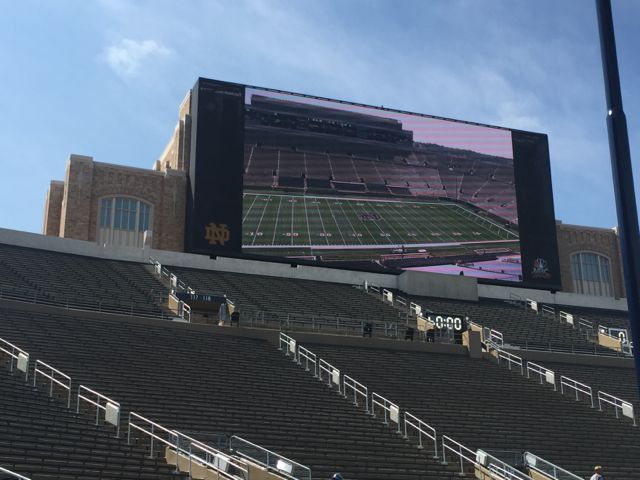

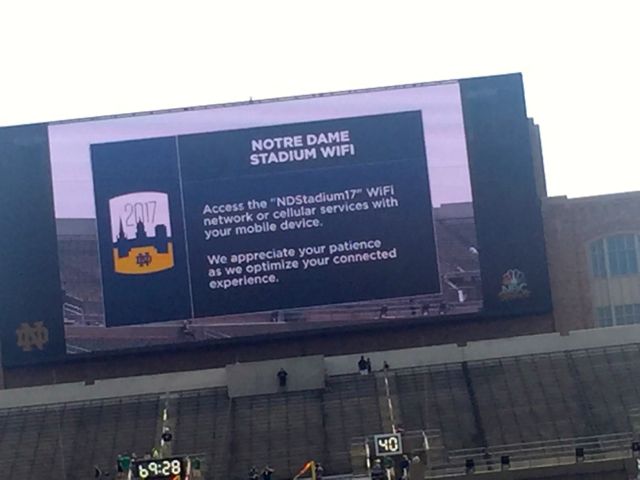

Though Wi-Fi deployment firm AmpThink has lately preferred railing Wi-Fi enclosures for proximate network builds, such as at Notre Dame, Langella said the Alamodome deployment will use more under-seat AP placements than railings, given the designed mobility of the Alamodome seating areas. “We have so much mobility with the stands, it’s hard to do lots of railing [placements],” Langella said.

According to Langella when the Wi-Fi deployment is finished — the network is scheduled to be fully completed by Dec. 1 — there will be approximately 750 APs installed, allowing the Alamodome to increase coverage from being able to serve 3,500 fans to being able to cover 65,000 fans, meaning every seat in the house. The improvements, he said, were part of a plan to attract the Final Four, which succeeded.

“We always thought we would improve the Wi-Fi,” Langella said. With the Final Four looming, he said, “we took the bull by the horns and got it done.”

Now that's one big TV! Behind the scenes: 1st video wall is all done and ready to be lifted! 233 days till #FinalFour pic.twitter.com/4PZpSXmIvK

— Final Four SATX (@FinalFour) August 9, 2017