Busch Stadium, St. Louis, home of a new MLBAM Wi-FI network. Credit all photos: St. Louis Cardinals

More than 740 Wi-Fi access points were installed to accommodate fans at Busch Stadium, including the AT&T Rooftop, as well the Busch II Infield and the Budweiser Brewhouse rooftop deck across Clark Ave. from the stadium at Ballpark Village, where the Cardinals played til 2005. The Cards’ wireless deployment was part of a $300 million initiative headed by MLBAM to build out Wi-Fi and DAS in all the league’s ballparks, with MLB, wireless carriers and teams all sharing in the costs. (While Busch may be the largest MLBAM deployment, AT&T Park in San Francisco has baseball’s most-dense Wi-Fi and DAS network by antenna numbers; the networks at AT&T Park are run by the Giants and AT&T.)

Yee said the Cardinals experienced relatively few engineering issues, in part because of the relative newness of the stadium. He also credited MLBAM, which took the Cardinals’ design and selected a systems integrator and an equipment vendor (Cisco).

“It’s a real turnkey solution where you submit the blueprint [to MLBAM] and they start locating the APs,” Yee said. “Where we come in is we have the background experience to tell the design team where people congregate and how often different spaces get used.”

Putting Wi-Fi in the railings

Editor’s note: This profile is from our most recent STADIUM TECH REPORT, the Q2 issue which contains a feature story on Wi-Fi analytics, and a sneak peek of the Minnesota Vikings’ new US Bank Stadium. DOWNLOAD YOUR FREE COPY today!

Wi-Fi railing enclosure.

“Over in Ballpark Village, we had brick on the outside of building so we had to be careful — that was an issue for the electricians to figure out,” Yee said, quickly adding that the electricians on projects like these rarely get the recognition they deserve. “The designer can say where the antennas go, but the electricians have to figure out how to get power to that spot and do it in a manner that fits the building,” he said.

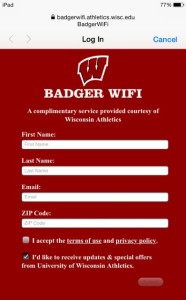

Cardinal fans trying to access the network hit a gated page that asks which cell carrier they use and also to accept terms and conditions; the Cardinals can then track usage and capacity by carrier and take that information back to the three carriers with DAS service in Busch Stadium: AT&T, Sprint and Verizon Wireless. “If Sprint, for example, notices they have lot more customers than anticipated, it might be time for them to review their capacity,” Yee said.

Cards director of IT Perry Yee

MLB app the center of activity focus

The Busch Stadium Wi-Fi network is new enough that MLBAM still is in the process of handing over management and oversight to the Cardinals’ organization; that makes it hard to track certain numbers — like what the budget was the for the project and how much money each entity contributed, numbers which MLBAM has not revealed for any of the many deployments it led throughout the league.

The Cardinals also aren’t releasing any official throughput or usage thresholds yet. Yee said he has seen speeds of 100 Mbps up and down and up on his Samsung S5 phone during more exciting parts of a recent game when fewer users were online. That number dipped to 20-30 Mbps during quieter parts of game. “It was a really good game — for half an hour no one was on the Wi-Fi, then when the score went in one direction I began to see speeds going down as people got online,” Yee said.

Lower level seats are covered with APs that shoot backwards into the stands.

The Cardinals have been using Bluetooth-based beacon technology for a couple years now. “We use it at our gates to greet people and it works via the Ballpark app,” Yee said. For now, the beaconing only works with iPhones; they’ll add support for Android devices at some point. But Yee foresees using beacon technology all around Busch Stadium at points of interest like the Stan Musial statue, providing information about who he was, what he did, to fans in proximity of the monument.

The Cardinals are still considering whether to deploy ambassadors in the stands during games to help people with connectivity issues and other questions. Longer term, they’re looking at geofencing with the concession areas or team store for specials and sale items — “Hot dogs on sale for this inning,” Yee mused. That’s way off in the future, the Cardinals’ IT director added.

In the meantime, the focus will be on “infrastructure that allows fans to see more and do more that makes the games more enjoyable,” Yee said.